Flyweight Design Pattern

Intent

- Use sharing to support large numbers of fine-grained objects efficiently.

- The Motif GUI strategy of replacing heavy-weight widgets with light-weight gadgets.

Problem

Designing objects down to the lowest levels of system "granularity" provides optimal flexibility, but can be unacceptably expensive in terms of performance and memory usage.

Discussion

The Flyweight pattern describes how to share objects to allow their use at fine granularity without prohibitive cost. Each "flyweight" object is divided into two pieces: the state-dependent (extrinsic) part, and the state-independent (intrinsic) part. Intrinsic state is stored (shared) in the Flyweight object. Extrinsic state is stored or computed by client objects, and passed to the Flyweight when its operations are invoked.

An illustration of this approach would be Motif widgets that have been re-engineered as light-weight gadgets. Whereas widgets are "intelligent" enough to stand on their own; gadgets exist in a dependent relationship with their parent layout manager widget. Each layout manager provides context-dependent event handling, real estate management, and resource services to its flyweight gadgets, and each gadget is only responsible for context-independent state and behavior.

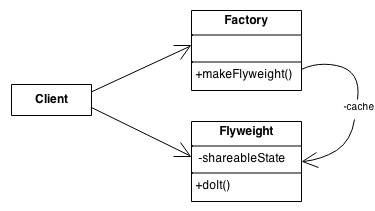

Structure

Flyweights are stored in a Factory's repository. The client restrains herself from creating Flyweights directly, and requests them from the Factory. Each Flyweight cannot stand on its own. Any attributes that would make sharing impossible must be supplied by the client whenever a request is made of the Flyweight. If the context lends itself to "economy of scale" (i.e. the client can easily compute or look-up the necessary attributes), then the Flyweight pattern offers appropriate leverage.

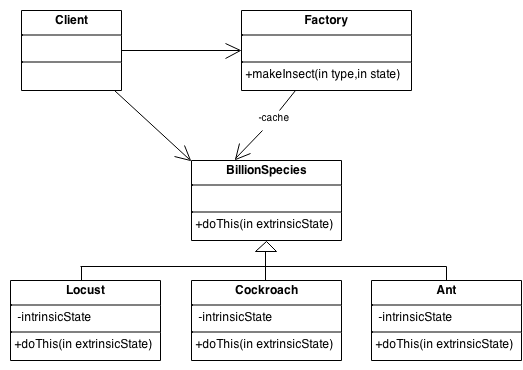

The Ant, Locust, and Cockroach

classes can be "light-weight" because their instance-specific state

has been de-encapsulated, or externalized, and must be supplied by

the client.

Example

The Flyweight uses sharing to support large numbers of objects efficiently. Modern web browsers use this technique to prevent loading same images twice. When browser loads a web page, it traverse through all images on that page. Browser loads all new images from Internet and places them the internal cache. For already loaded images, a flyweight object is created, which has some unique data like position within the page, but everything else is referenced to the cached one.

Check list

- Ensure that object overhead is an issue needing attention, and, the client of the class is able and willing to absorb responsibility realignment.

- Divide the target class's state into: shareable (intrinsic) state, and non-shareable (extrinsic) state.

- Remove the non-shareable state from the class attributes, and add it the calling argument list of affected methods.

- Create a Factory that can cache and reuse existing class instances.

- The client must use the Factory instead of the new operator to request objects.

- The client (or a third party) must look-up or compute the non-shareable state, and supply that state to class methods.

Rules of thumb

- Whereas Flyweight shows how to make lots of little objects, Facade shows how to make a single object represent an entire subsystem.

- Flyweight is often combined with Composite to implement shared leaf nodes.

- Terminal symbols within Interpreter's abstract syntax tree can be shared with Flyweight.

- Flyweight explains when and how State objects can be shared.