Composite Design Pattern

Intent

- Compose objects into tree structures to represent whole-part hierarchies. Composite lets clients treat individual objects and compositions of objects uniformly.

- Recursive composition

- "Directories contain entries, each of which could be a directory."

- 1-to-many "has a" up the "is a" hierarchy

Problem

Application needs to manipulate a hierarchical collection of "primitive" and "composite" objects. Processing of a primitive object is handled one way, and processing of a composite object is handled differently. Having to query the "type" of each object before attempting to process it is not desirable.

Discussion

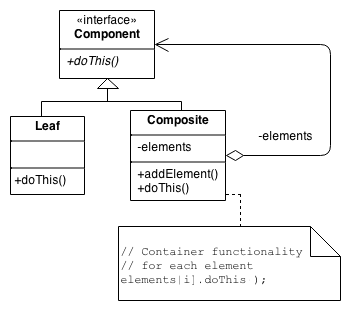

Define an abstract base class (Component) that specifies the behavior that needs to be exercised uniformly across all primitive and composite objects. Subclass the Primitive and Composite classes off of the Component class. Each Composite object "couples" itself only to the abstract type Component as it manages its "children".

Use this pattern whenever you have "composites that contain components, each of which could be a composite".

Child management methods [e.g. addChild(), removeChild()] should

normally be defined in the Composite class. Unfortunately, the desire

to treat Primitives and Composites uniformly requires that these

methods be moved to the abstract Component class. See the "Opinions"

section below for a discussion of "safety" versus "transparency"

issues.

Structure

Composites that contain Components, each of which could be a Composite.

Menus that contain menu items, each of which could be a menu.

Row-column GUI layout managers that contain widgets, each of which could be a row-column GUI layout manager.

Directories that contain files, each of which could be a directory.

Containers that contain Elements, each of which could be a Container.

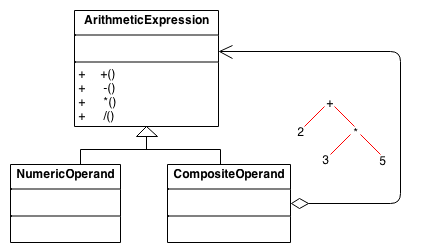

Example

The Composite composes objects into tree structures and lets clients treat individual objects and compositions uniformly. Although the example is abstract, arithmetic expressions are Composites. An arithmetic expression consists of an operand, an operator (+ - * /), and another operand. The operand can be a number, or another arithmetic expression. Thus, 2 + 3 and (2 + 3) + (4 * 6) are both valid expressions.

Check list

- Ensure that your problem is about representing "whole-part" hierarchical relationships.

- Consider the heuristic, "Containers that contain containees, each of which could be a container." For example, "Assemblies that contain components, each of which could be an assembly." Divide your domain concepts into container classes, and containee classes.

- Create a "lowest common denominator" interface that makes your containers and containees interchangeable. It should specify the behavior that needs to be exercised uniformly across all containee and container objects.

- All container and containee classes declare an "is a" relationship to the interface.

- All container classes declare a one-to-many "has a" relationship to the interface.

- Container classes leverage polymorphism to delegate to their containee objects.

- Child management methods [e.g.

addChild(),removeChild()] should normally be defined in the Composite class. Unfortunately, the desire to treat Leaf and Composite objects uniformly may require that these methods be promoted to the abstract Component class. See the Gang of Four for a discussion of these "safety" versus "transparency" trade-offs.

Rules of thumb

- Composite and Decorator have similar structure diagrams, reflecting the fact that both rely on recursive composition to organize an open-ended number of objects.

- Composite can be traversed with Iterator. Visitor can apply an operation over a Composite. Composite could use Chain of Responsibility to let components access global properties through their parent. It could also use Decorator to override these properties on parts of the composition. It could use Observer to tie one object structure to another and State to let a component change its behavior as its state changes.

- Composite can let you compose a Mediator out of smaller pieces through recursive composition.

- Decorator is designed to let you add responsibilities to objects without subclassing. Composite's focus is not on embellishment but on representation. These intents are distinct but complementary. Consequently, Composite and Decorator are often used in concert.

- Flyweight is often combined with Composite to implement shared leaf nodes.

Opinions

The whole point of the Composite pattern is that the Composite can be treated atomically, just like a leaf. If you want to provide an Iterator protocol, fine, but I think that is outside the pattern itself. At the heart of this pattern is the ability for a client to perform operations on an object without needing to know that there are many objects inside.

Being able to treat a heterogeneous collection of objects atomically (or transparently) requires that the "child management" interface be defined at the root of the Composite class hierarchy (the abstract Component class). However, this choice costs you safety, because clients may try to do meaningless things like add and remove objects from leaf objects. On the other hand, if you "design for safety", the child management interface is declared in the Composite class, and you lose transparency because leaves and Composites now have different interfaces.

Smalltalk implementations of the Composite pattern usually do not have the interface for managing the components in the Component interface, but in the Composite interface. C++ implementations tend to put it in the Component interface. This is an extremely interesting fact, and one that I often ponder. I can offer theories to explain it, but nobody knows for sure why it is true.

My Component classes do not know that Composites exist. They provide

no help for navigating Composites, nor any help for altering the

contents of a Composite. This is because I would like the base class

(and all its derivatives) to be reusable in contexts that do not

require Composites. When given a base class pointer, if I absolutely

need to know whether or not it is a Composite, I will use dynamic_cast

to figure this out. In those cases where dynamic_cast is too

expensive, I will use a Visitor.

Common complaint: "if I push the Composite interface down into the Composite class, how am I going to enumerate (i.e. traverse) a complex structure?" My answer is that when I have behaviors which apply to hierarchies like the one presented in the Composite pattern, I typically use Visitor, so enumeration isn't a problem - the Visitor knows in each case, exactly what kind of object it's dealing with. The Visitor doesn't need every object to provide an enumeration interface.

Composite doesn't force you to treat all Components as Composites. It merely tells you to put all operations that you want to treat "uniformly" in the Component class. If add, remove, and similar operations cannot, or must not, be treated uniformly, then do not put them in the Component base class. Remember, by the way, that each pattern's structure diagram doesn't define the pattern; it merely depicts what in our experience is a common realization thereof. Just because Composite's structure diagram shows child management operations in the Component base class doesn't mean all implementations of the pattern must do the same.