Design Patterns

In software engineering, a design pattern is a general repeatable solution to a commonly occurring problem in software design. A design pattern isn't a finished design that can be transformed directly into code. It is a description or template for how to solve a problem that can be used in many different situations.

Uses of Design Patterns

Design patterns can speed up the development process by providing tested, proven development paradigms. Effective software design requires considering issues that may not become visible until later in the implementation. Reusing design patterns helps to prevent subtle issues that can cause major problems and improves code readability for coders and architects familiar with the patterns.

Often, people only understand how to apply certain software design techniques to certain problems. These techniques are difficult to apply to a broader range of problems. Design patterns provide general solutions, documented in a format that doesn't require specifics tied to a particular problem.

In addition, patterns allow developers to communicate using well-known, well understood names for software interactions. Common design patterns can be improved over time, making them more robust than ad-hoc designs.

Creational design patterns

These design patterns are all about class instantiation. This pattern can be further divided into class-creation patterns and object-creational patterns. While class-creation patterns use inheritance effectively in the instantiation process, object-creation patterns use delegation effectively to get the job done.

-

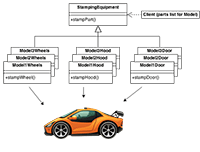

Abstract Factory

Creates an instance of several families of classes -

Builder

Separates object construction from its representation -

Factory Method

Creates an instance of several derived classes -

Object Pool

Avoid expensive acquisition and release of resources by recycling objects that are no longer in use - Prototype

A fully initialized instance to be copied or cloned - Singleton

A class of which only a single instance can exist

Structural design patterns

These design patterns are all about Class and Object composition. Structural class-creation patterns use inheritance to compose interfaces. Structural object-patterns define ways to compose objects to obtain new functionality.

-

Adapter

Match interfaces of different classes -

Bridge

Separates an object’s interface from its implementation -

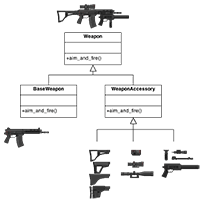

Composite

A tree structure of simple and composite objects -

Decorator

Add responsibilities to objects dynamically -

Facade

A single class that represents an entire subsystem -

Flyweight

A fine-grained instance used for efficient sharing -

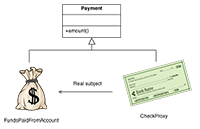

Private Class Data

Restricts accessor/mutator access - Proxy

An object representing another object

Behavioral design patterns

These design patterns are all about Class's objects communication. Behavioral patterns are those patterns that are most specifically concerned with communication between objects.

-

Chain of responsibility

A way of passing a request between a chain of objects - Command

Encapsulate a command request as an object -

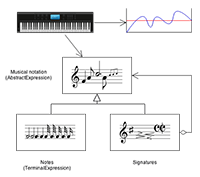

Interpreter

A way to include language elements in a program -

Iterator

Sequentially access the elements of a collection -

Mediator

Defines simplified communication between classes -

Memento

Capture and restore an object's internal state -

Null Object

Designed to act as a default value of an object - Observer

A way of notifying change to a number of classes -

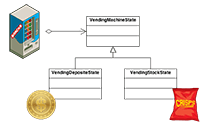

State

Alter an object's behavior when its state changes - Strategy

Encapsulates an algorithm inside a class -

Template method

Defer the exact steps of an algorithm to a subclass -

Visitor

Defines a new operation to a class without change

Criticism

The concept of design patterns has been criticized by some in the field of computer science.

Targets the wrong problem

The need for patterns results from using computer languages or techniques with insufficient abstraction ability. Under ideal factoring, a concept should not be copied, but merely referenced. But if something is referenced instead of copied, then there is no "pattern" to label and catalog. Paul Graham writes in the essay Revenge of the Nerds.

Peter Norvig provides a similar argument. He demonstrates that 16 out of the 23 patterns in the Design Patterns book (which is primarily focused on C++) are simplified or eliminated (via direct language support) in Lisp or Dylan.

Lacks formal foundations

The study of design patterns has been excessively ad hoc, and some have argued that the concept sorely needs to be put on a more formal footing. At OOPSLA 1999, the Gang of Four were (with their full cooperation) subjected to a show trial, in which they were "charged" with numerous crimes against computer science. They were "convicted" by ⅔ of the "jurors" who attended the trial.

Leads to inefficient solutions

The idea of a design pattern is an attempt to standardize what are already accepted best practices. In principle this might appear to be beneficial, but in practice it often results in the unnecessary duplication of code. It is almost always a more efficient solution to use a well-factored implementation rather than a "just barely good enough" design pattern.

Does not differ significantly from other abstractions

Some authors allege that design patterns don't differ significantly from other forms of abstraction, and that the use of new terminology (borrowed from the architecture community) to describe existing phenomena in the field of programming is unnecessary. The Model-View-Controller paradigm is touted as an example of a "pattern" which predates the concept of "design patterns" by several years. It is further argued by some that the primary contribution of the Design Patterns community (and the Gang of Four book) was the use of Alexander's pattern language as a form of documentation; a practice which is often ignored in the literature.